What If.

It started with a small surprise.

While walking through my neighborhood in East Willowdale, a quiet suburban pocket of Toronto, I noticed a convenience store tucked neatly into the middle of a residential block. It wasn’t on a main street. It wasn’t part of a plaza. It was just… there. Quiet, underused, and clearly out of place, at least in planning terms.

Out of curiosity, I checked the City of Toronto’s zoning bylaw map. As expected, the entire area was zoned “Neighbourhoods,” which typically prohibits any commercial or retail uses. So how was this store even allowed?

That one oddity sparked a bigger question in my mind, and this post is my way of thinking it through.

As a recent graduate in urban planning, I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about how we can reduce car dependency, promote active transportation, and bring more livability into our suburbs. But time and time again, I run into the same issue: our zoning laws, especially in low-rise areas, often make even small improvements difficult.

Across Ontario, planners, policymakers, and communities are working toward the same major goals: reducing car dependency, lowering emissions, and building more sustainable cities. But for those of us who believe in these objectives, we quickly realize the path to achieving them isn’t just about better transit systems or energy-efficient buildings. It’s also about rethinking how neighborhoods function on a day-to-day level.

And yet, the existing planning framework makes even small shifts incredibly difficult. Introducing a local gym, a co-working space, or a shared studio within walking distance sounds simple enough, until you hit a wall of regulations. These policies are built on a specific vision of the city, one shaped over decades by a North American ideal that prioritized large-scale suburban development, wide separations between uses, and heavy reliance on cars. In many places, the infrastructure now reinforces this layout: vast stretches of low-density housing, isolated community hubs, and few destinations within reach by foot or bike.

So what if we allowed a little more? Not a massive transformation or top-down reshaping of our communities, but simply the space for a neighborhood to evolve if it wants to. What if zoning offered more flexibility, and people had the option to introduce a gym, a dental clinic, or a small café into their block, not imposed, but possible?

This isn’t a call for radical change. I’m not arguing we should bulldoze homes to build cafés, gyms, or co-working spaces. What I’m asking is: what if we allowed just a little more? What if small-scale, local-serving commercial uses, like a dental clinic, a daycare, or yes, a better version of that convenience store, were permitted in moderation, within walking distance in neighborhoods like mine?

Let’s allow room for these decisions to come from within the community, not dictated from above. And maybe, as planners, our role isn’t just to implement what’s written, but to listen.

Willowdale convenience location

Understanding the Problem

The moment I saw that one convenience store tucked inside a block of homes in East Willowdale, it felt like a small urban glitch. A surprise. But then I asked myself: why does it feel like a surprise? Shouldn’t it be normal to have places for small daily needs within walking distance in our neighborhoods?

The answer lies mostly in our zoning by-laws and the planning frameworks that shape how we build our cities.

Across Ontario (and broadly across Canada), the Planning Act sets the foundation for municipal decision-making. Local municipalities like Toronto are then required to develop Official Plans, which establish high-level land use directions for how and where we grow. These plans are implemented through more detailed zoning by-laws, and this is where the everyday reality of our neighborhoods is locked in.

In Toronto, neighborhoods like East Willowdale are typically zoned as “Neighbourhoods” (yellow zones). These zones are primarily reserved for low-rise residential uses like detached and semi-detached homes, with a few exceptions such as schools, churches, or community centres. Even small, quiet commercial uses, such as a gym, dental office, or co-working space, are often not permitted as-of-right. In many cases, any deviation from the strict land use designation requires a lengthy and uncertain process: rezoning, Official Plan amendments, community consultations, and sometimes appeals at the Ontario Land Tribunal.

This rigid separation of uses is part of a broader planning legacy rooted in post-war suburban development, heavily influenced by the North American ideal of the “quiet, car-oriented lifestyle.” The American Dream, as it took form in urban planning, imagined single-family homes on large lots, with personal vehicles as the main tool for accessing work, shopping, or services. Over time, this shaped vast suburban areas where walking became impractical and daily life revolved around driving.

East Willowdale, while part of a major global city, still reflects this structure. Streets are calm, lined with homes, but intentionally lack a mix of uses. The very absence of places to walk to is what reinforces our dependence on cars, even for short trips. And while many people might want to walk or bike more, the physical layout of their neighborhood and the rules embedded in zoning by-laws simply don’t support that choice.

This isn’t just about planning policy, it’s about lived experience. When we talk about encouraging active transportation or building more walkable communities, we need to confront how our existing land use frameworks limit what kind of places can exist in our neighborhoods. The problem isn’t just what’s not allowed; it’s that the tools to try something new are often too slow, too complicated, or too risky for smaller businesses or community groups to attempt.

In short, the policy structure and the urban form are working together to keep things exactly as they are, even when residents and planners agree that more livability and accessibility would be a good thing.

Accessibility on the Ground: The East Willowdale Picture

The planning constraints we explored in Section 2 aren’t just lines in a by-law document, they have left a visible imprint on how East Willowdale works. Decades of zoning policy, the dominance of single-use residential design, and the suburban ideals that shaped much of North American planning have created a familiar pattern: daily needs clustered along a few mixed-use corridors, while large pockets of the neighborhood remain purely residential.

In practice, this means accessibility is uneven. Residents living close to Yonge Street, Sheppard Avenue, or Bayview Avenue enjoy a variety of shops, services, and amenities within walking distance. But for those deeper inside the neighborhood’s low-rise interior, the same destinations often require a drive. The urban form simply does not support a balanced mix of land uses across the area, and the street network itself was never designed for easy, direct active transportation connections between homes and amenities.

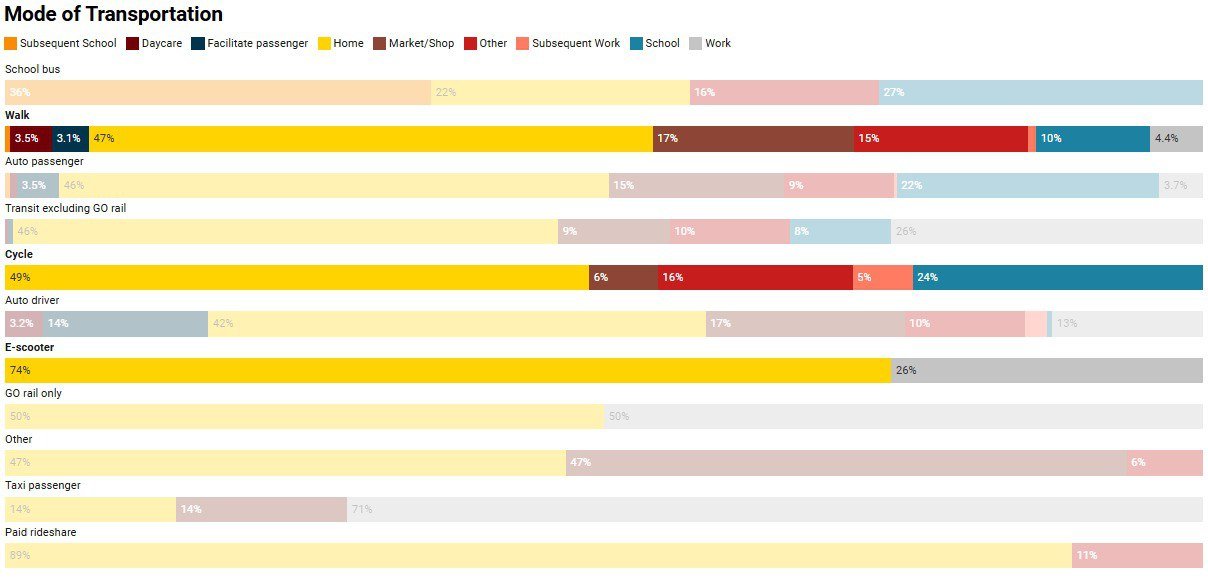

This imbalance directly influences travel behaviours, and it shows in the data. The Transportation Tomorrow Survey (TTS) data for East Willowdale reveals that for many everyday trips, active transportation plays only a small role. For example, trips to markets or shops are dominated by driving, with only a small share made by walking or cycling. Even short errands, like going to the library, gym, or a small convenience store, are often taken by car, reflecting the fact that such amenities are not evenly distributed within the neighborhood.

Cycling and walking are still present in the data, but not in the volumes we might expect if amenities were more local and the network more supportive of active travel. While some residents can and do walk to work, school, or errands, this tends to be concentrated in areas near the mixed-use corridors. For many others, the distances, disconnected street grid, and lack of intermediate destinations make these trips impractical without a vehicle.

In short, the accessibility challenge in East Willowdale isn’t simply about personal choice or habit. It’s the result of decades of planning decisions, reinforced by zoning rules, that concentrate activity in narrow strips while leaving much of the surrounding neighborhood with no realistic alternative to the car for most daily needs.

Transportation Tomorrow Survey data

Imagine arriving home after a long day at work. You want to go to the gym. However, the gym is located along major corridors like Yonge Street, which means getting back into the car and driving there. At that point, fatigue and distance make it much easier to choose the car over other options. But if a local gym were available within the neighborhood, just a few blocks away, you might instead consider walking or cycling. In this way, the very location of facilities like gyms can encourage or discourage people from choosing active transportation.

Beyond fitness facilities, a variety of other small-scale, low-density services can be introduced to strengthen the neighborhood’s livability. Local amenities such as co-working or shared office spaces, pharmacies, hair salons, cafés, or corner stores provide residents with convenient options without the need for long commutes. These services are not high-intensity uses, but they play a critical role in shaping a more complete and resilient community fabric.

The growing importance of remote and flexible work makes co-working spaces particularly valuable. Rather than isolating work strictly within the home, a shared workspace nearby offers opportunities for collaboration, networking, and productivity in a professional yet accessible environment. For many, this represents a middle ground, not the long commute to a distant office, but not the full solitude of working at the kitchen table either. Incorporating spaces like these reflects today’s changing patterns of work and responds to real community needs.

Together, these types of amenities align closely with the principles of the “15-minute city.” The goal is to ensure that essential daily needs, from exercise and work to groceries and personal care, can be met within a short walk or bike ride from home. This concept emphasizes not only convenience, but also equity, sustainability, and quality of life. By carefully planning for such services, the neighborhood becomes more vibrant, connected, and inclusive.

Importantly, achieving this vision does not mean bulldozing existing structures or imposing radical interventions. Instead, it is about carefully weaving new amenities into the existing urban fabric. This incremental approach respects the character of the neighborhood while still creating meaningful improvements. By focusing on thoughtful integration, the community evolves in a way that feels natural, sustainable, and widely supported.

Conclusion

That simple convenience store, tucked into a suburban street, reminded me that small interventions can have an outsized impact on how people interact with their neighborhood. It showed that even modest, everyday uses can shape patterns of movement, create opportunities for casual encounters, and bring a sense of vitality to otherwise predictable streetscapes. When we talk about planning and zoning, it’s easy to get caught up in large-scale strategies or long-term visions — but sometimes it is the smallest, most ordinary elements that reveal how adaptable and resilient our neighborhoods can be.

Imagining more of these small-scale, community-serving uses in suburban areas raises important questions about flexibility, balance, and the potential for change without losing stability. It doesn’t mean tearing apart what exists, but rather exploring how small allowances might open the door to more livable, connected, and engaging communities.

And yet, I should emphasize that these are simply the thoughts of someone at the beginning of his journey as a planner who is still learning, still questioning, and still curious about the many debates that shape urban planning. This post is not meant to be a professional statement or a formal report, but rather a reflection born out of observation and passion for the field.

References

City of Toronto. (2023). Population of neighbourhoods 2021. City of Toronto. https://www.toronto.ca/city-government/data-research-maps/neighbourhoods-communities/population-of-neighbourhoods-2021/

City of Toronto. (2024). TTC subway ridership. City of Toronto. https://www.toronto.ca/city-government/data-research-maps/research-reports/transportation/ttc-subway-ridership/

Statistics Canada. (2023). Greenhouse gas emissions, by economic sector. Government of Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/12-581-x/2023001/sec18-eng.htm

University of the Built Environment. (2023). A guide to 15-minute cities: Why are they so controversial? UBE. https://www.ube.ac.uk/whats-happening/articles/15-minute-city/